Running northward from Court Square, Pleasant Street was originally known as the New Haven Road and served in earlier times as it does now as the principal entry to the village from the north. Here were located from the start the homes of the professionals who would bring status to Middlebury and the craftsmen who would supply the town’s needs for quality goods. Here, adjacent to the Green, Painter quickly deeded lots to such people as a lawyer, a doctor, a cabinetmaker, and a blacksmith. In time a series of quiet elegant buildings were constructed in the area.

17 23 North Pleasant Street This fine brick structure was built in 1816 as a store for Thomas Hagar and subsequently housed the National Bank of Middlebury until its move to new quarters across the Green in 1911. The second floor was occupied for many years by the predecessor of Middlebury’s public library, the Ladies’ Library, founded in the 1860s. In the course of its history the building had a balustraded (text with tooltip) a row of short pillars topped by a rail roof line; first a Federal, (text with tooltip) a term generally designating the American architecture of the late eighteenth and early 19th centuries and here used with particular reference to the architectural fashion emanating from Boston at this time. It is characterized by planar simplicity and a refined delicacy in proportions and detailing. Decorative details (akin to those of the English Adam style and Wedgewood china) are ancient Roman in their inspiration. Perhaps the most characteristic feature of the style is a doorway composition with a fan light and sidelights then a Greek Revival, and then a Victorian doorway; and shared with the inn a beautiful stretch of cast-iron fence toward the Green.

18 Inn Annex The brick house just north of the Inn and bank was erected in 1825 for Jonathan Wainwright, whose brother Rufus purchased the Painter mansion not long after Gamaliel’s death in 1819. The brothers were merchants and owned a foundry, first in Frog Hollow and later near Pulp Mill Bridge, where they cast (among other things) the widely-sold Wainwright stove. Jonathan’s house was both substantial and soberly elegant with its great brick mass, even rhythm of windows, and beautifully proportioned and detailed doorway. This last is noteworthy for its fine leaded fan (text with tooltip) fan light: an arched window with radiating muntins, often above a door and side lights (text with tooltip) the narrow vertical windows flanking a door and its sophisticated combination of pilasters and colonnettes. Beyond this doorway are to be found molded ceilings, paneled window embrasures, classically detailed marble fireplaces, and one of Middlebury’s finest curving staircases. In 1881 Smith and Allen remodeled the house, changing the gabled roof into a fashionable Second Empire (text with tooltip) a style of architecture inspired by official building in Paris under Napoleon III and typified by mansard roofs and oft-elaborate dormers. It was popular in America in the decades following the Civil War mansard (text with tooltip) a double-sloped roof, the lower portion being longer and steeper than the upper. It is named for the French architect Francois Mansart and was a major device of the Second Empire style and adding the Palladian window, (text with tooltip) a three-part window with a central arch between rectangular side openings. Popular in the sixteenth century in Italy, it was picked up by the English in the eighteenth century. It is also called the Venetian or Serlian window. the bay window toward the inn, and the dominating piazza. (text with tooltip) the name given to the large porches of the later 19th century because of their similarity to the arcades and colonnades which often surround an Italian square (or piazza) The house remained a residence for prominent Middlebury families until its purchase in 1941 as an annex for the inn.

19 Charter House In 1789 Painter deeded a lot on the New Haven Road (just north of the later Wainwright House) to Samuel Miller, a lawyer from Springfield, MA. Here Miller built first a small law office and then his home. Not only a leading and reputedly very courtly lawyer, but also representative to the General Assembly in 1797 and recipient of an honorary degree from Yale, Miller was a prominent participant in the affairs of his new town. On September 30, 1798, he was host to a meeting in his home that was to have long-lasting significance to the community. Timothy Dwight, president of Yale, was stopping off briefly at the home of his friend, the Middlebury lawyer Seth Storrs. Storrs quickly gathered the trustees of the newly chartered Addison County Grammar School and, in conference at Miller’s house and with Dwight’s advice and encouragement, they determined to apply for a charter for Middlebury College with a curriculum modelled on that of Yale. As a result the house came to be known as Charter House.

A building much altered and augmented, Charter House seems to defy precise dating and discussion. The 1789 law office was most likely shifted to the rear to make room for the newer front structure of the 1790s. This had a hipped roof, (text with tooltip) a roof with sloped rather than vertical ends which still exists beneath its mid-century gabled slate roof, and most likely a center chimney and a straight-headed Palladian window. (text with tooltip) a three-part window with a central arch between rectangular side openings. Popular in the sixteenth century in Italy, it was picked up by the English in the eighteenth century. It is also called the Venetian or Serlian window. After Miller’s death in 1810, the house was purchased by Edward D. Barber, who purportedly altered it extensively. Under Barber and later owners it received its mix of fine Federal, (text with tooltip) a term generally designating the American architecture of the late eighteenth and early 19th centuries and here used with particular reference to the architectural fashion emanating from Boston at this time. It is characterized by planar simplicity and a refined delicacy in proportions and detailing. Decorative details (akin to those of the English Adam style and Wedgewood china) are ancient Roman in their inspiration. Perhaps the most characteristic feature of the style is a doorway composition with a fan light and sidelights Greek Revival, Victorian and Colonial Revival details. Particularly noteworthy are the leaded glass of the front door, the beautiful fireplaces with eagles, urns, and swags in the front parlors, and the fine interior door casings. In 1970 the house, which had fallen into sad disrepair, was purchased by the Congregational Church, laudably renovated, and restored to a significant place in the life of the community. Since 2009 it has been managed by the Charter House Coalition as a center providing meals and emergency housing.

20 31 North Pleasant Street To the north of Sam Miller was originally the lot of Dr. Matthews, and to the north of that a double lot originally deeded to William Young, Middlebury’s first cabinetmaker. On this latter site, in 1805, was built the house of lawyer, businessman, selectman, and college officer John Simmons. A graduate of Brown University, Simmons established his Middlebury law practice in 1801, and in 1804 compiled The Law Magazine, the first book of legal forms ever published in Vermont.

His house is significant both for its plan and for its elegant detailing. The typical prestigious residence of the eighteenth century had been broadside to the road with a central doorway, either a central chimney mass or center hall, and major rooms to either side. Simmons’ house is an early example of a more townhouse-like plan that would become popular in Middlebury in the first third of the nineteenth century. It is arranged with its narrow, or gable, end toward the road. An off-center entrance and staircase occupy a front corner of the house, and chambers are arranged to one side and the back of a central chimney mass. The gable is treated as a pediment (text with tooltip) a low-pitched gable defined to read as a triangle by cornices or moldings and decorated with fine rope and dentil (text with tooltip) a small square block used in evenly-spaced series for Ionic and Corinthian cornices moldings. Set into it is a gracefully- muntined (text with tooltip) a dividing element between the panes of a window elliptical attic window with a star-shaped central decoration. The doorway (beneath the Victorian porch) is typically deep-set with paneled returns (text with tooltip) return: an element running back at right angles to the face of a structure and a semicircular fanlight. (text with tooltip) an arched window with radiating muntins, often above a door Within are three of four very fine original fireplaces with dentils, (text with tooltip) small square blocks used in evenly-spaced series for Ionic and Corinthian cornices sunbursts, and pilasters. Not as grand, perhaps, as the Painter and Wainwright houses, it was without a doubt one of Middlebury’s most sophisticated residences.

21 37 North Pleasant Street This Federal (text with tooltip) a term generally designating the American architecture of the late eighteenth and early 19th centuries and here used with particular reference to the architectural fashion emanating from Boston at this time. It is characterized by planar simplicity and a refined delicacy in proportions and detailing. Decorative details (akin to those of the English Adam style and Wedgewood china) are ancient Roman in their inspiration. Perhaps the most characteristic feature of the style is a doorway composition with a fan light and sidelights -Greek Revival style house, built in 1803 by local merchant Joseph Dorrance, on a site previously owned by Cyrus Brewster, later became the residence of Vermont governor William Slade. The main features include a Georgian (text with tooltip) the high style of eighteenth-century America. It is often characterized by formal symmetry and robust detailing (this latter including doors with transoms but no side lights, quoins, pilasters, and Palladian windows) plan, sidelights, (text with tooltip) the narrow vertical windows flanking a door transom, paneled entry pilasters, entry entablature and a Queen Anne porch.

22 39 North Pleasant Street One of Middlebury’s few surviving early hipped-roof (text with tooltip) a roof with sloped rather than vertical ends houses, this structure was the first (1804) of three houses in the neighborhood built and lived in by blacksmith Ruluff Lawrence. His first house was built on the site of a 1793 home of Dr. Joseph Clark that was moved to Seminary Street. Much altered inside, Lawrence’s two-story Federal (text with tooltip) a term generally designating the American architecture of the late eighteenth and early 19th centuries and here used with particular reference to the architectural fashion emanating from Boston at this time. It is characterized by planar simplicity and a refined delicacy in proportions and detailing. Decorative details (akin to those of the English Adam style and Wedgewood china) are ancient Roman in their inspiration. Perhaps the most characteristic feature of the style is a doorway composition with a fan light and sidelights style house still has a staircase that agrees in detailing with his 11 Seminary Street house. Other features include a Georgian (text with tooltip) the high style of eighteenth-century America. It is often characterized by formal symmetry and robust detailing (this latter including doors with transoms but no side lights, quoins, pilasters, and Palladian windows) plan, leaded glass, sidelights, (text with tooltip) the narrow vertical windows flanking a door transom, cornice (text with tooltip) the horizontal projection (often the edge of a roof and usually faced with moldings) which caps a wall composition caps, and a distinctive porch.

23 United Methodist Church In 1805 Hastings Warren purchased this lot from Daniel Chipman and built a cabinet shop. Warren was the son-in-law and successor in business to William Young, Middlebury’s first cabinetmaker, and pursued his trade well into the 19th century, filling the local papers with ads for “sideboards, commodes, secretaries, bookcases, bureaus, wardrobes, tables, chairs, clock-cases,” etc. The Henry Sheldon Museum contains interesting examples of his fine work. During the war of 1812, Warren, who achieved the rank of General, mustered and led the local troops for the Battle of Plattsburgh. As recounted in Swift’s History of Middlebury:

“He came on to the village common, followed by martial music, and invited all who were so disposed to join him as volunteers. After marching once or twice around the common, forty or fifty men had fallen into the ranks, and the number was afterwards increased. When a dozen or two were ready to start with him, they marched for the field of battle, and others, as fast they were ready, followed.”

Warren’s first shop burned, as did its successor. In 1815, therefore, he went “fireproof,” building a fine two-story brick structure next door (9 Seminary Street — demolished in 1975).

Warren was among the earliest members of the Methodist Society in Middlebury, served by a rider from the Vergennes Circuit since 1798. By 1801 early meetings were held in the home of Lebbeus Harris, son-in-law and business partner of Eben Judd and later co-resident of the Judd-Harris House (now home to the Sheldon Museum). Under the encouragement of Francis Asbury (the first American Methodist bishop, who preached in town in 1810), in 1813 the Methodists built a chapel on land owned by Warren at the corner of Seymour Street and Methodist Lane. The denomination favored by Middlebury’s mill workers, having outgrown their chapel, the Methodists built a new church in 1837 on the North Pleasant Street site of Warren’s former workshop and sold their old home to the Baptists. The new frame church was constructed by Asahel Parsons, builder in 1836 of the college’s Old Chapel and in 1838 of the Salisbury Congregational Church. The very similar Middlebury and Salisbury churches shared a distinctive tapered spire, identical to one (now lost) designed for Winooski in 1836 by Burlington-based Ammi B. Young, author of the Vermont Statehouse and likely the source of Parson’s designs.

This building burned in 1891, its 1880s pulpit furniture (still in use) saved by throwing it out a window of the blazing building. It was replaced by the present structure in 1892–1893. The plans for the new building were drawn by Valk and Son of Brooklyn, N. Y.; but not entirely satisfying the congregation, they were altered by church member Clinton Smith, then resident in Washington, DC, as head of construction for the War Department. His firm of Smith and Piper built the edifice. It is a design in which materials and forms are used with vigor and unity to express emphatically the forces at work in the architecture. Much under the influence of the work of Henry Hobson Richardson, it combines Weybridge bluestone, Willard redstone, brick, and slate, a vigorously massed tower, a strongly expressed stone base from which rise swelling brackets to “carry” the load of the dominating roof, and Shingle-Style, (text with tooltip) a style of architecture popular (especially for domestic and medium-sized buildings) from the late 1870s through the end of the 19th century. It is characterized by dominant roofs and the pervasive use of shingles or shingle-like textures on vertical as well as inclined surfaces. slate-covered gable ends. The non-figural opal and jeweled stained glass, fabricated by the Tyndall Art Glass Company of Washington, DC, has small horizontal modules that resonate with the texture of the building’s brick and slate work. Furnished with a pipe organ by the Hutchins Company of Boston (which arrived in 64 cases) and a bell from the USS Alaska (on extended loan from the U. S. Navy), the building is one of the most sophisticated Queen Anne (late Victorian) churches in Vermont.

Cross to the west side of North Pleasant Street and head back towards the center of the village.

24 56 North Pleasant Street The home of Havurah (Addison County Jewish Congregation) is a handsome Italianate (text with tooltip) referring to one of the picturesque vocabularies drawn upon by builders in the middle quarters of the 19th century. Inspired particularly by Tuscan villas, “Italian” details included heavy cornices, elaborate brackets, towers or belvederes, round arched windows, and heavily plastic moldings house with an expansive Queen Anne porch built in 1876 as the residence of the Cook family. However, it was best known and owes its present status to its longest term residents, the Lazarus family. Reputedly the first Jewish family in Middlebury, Harry and Stella Lazarus arrived from Mineville, N.Y., about 1913 and opened a department store on Main Street that would be a town fixture for the next 75 years. Their sons Eugene (“Mike”) and Stanton were star athletes in high school who, after university and military service in World War II, returned to play a prominent role in the life of Middlebury as merchants and public officials. The entire family was central to the development of an evolving Jewish community that included survivors of the war in Europe, members of the business and professional community, and students and faculty at the college. The family welcomed students to their home for Friday evening dinners and holiday celebrations. In 1981 the growing community organized as Chavurah: the Addison County Jewish Congregation. Following Stan’s death, in 1999 Mike donated the family home to become Havurah House. After extensive renovations and addition by local architect Parker Croft, the congregation occupied their new home in 2001.The former Lazarus living room is now the sanctuary, outfitted with an ark and reader’s table and library shelves dedicated to long-time Ripton summer resident and friend of Robert Frost, Rabbi Victor Reichert.

25 30 North Pleasant Street Former site of the “pebble house,” an interesting frame house built in two sections — the earlier, southern half by Loudon Case, the later northern half by Olcott White in or soon after 1807 to house his book bindery and shop. In the 20th century its lower floor was wrapped in pebble masonry and the second floor in stucco, leaving only dentil (text with tooltip) a small square block used in evenly-spaced series for Ionic and Corinthian cornices moldings beneath the eaves, an attic window, and handsome chimneys to witness its former quality. In 2016–2017 it was replaced with a two-story office and Sunday School annex for the Congregational Church by Smith Alvarez Sienkiewycz Architects of Burlington.

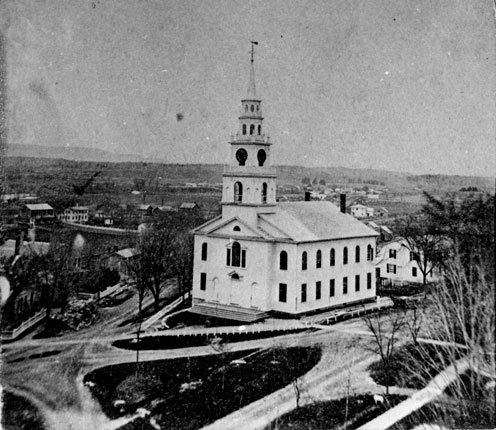

26 Congregational Church The prominent site at what is now the intersection of Main, Seymour, and North Pleasant Streets was not always that of the Congregational Church. It was originally deeded by Painter in 1789 to John Deming for the construction of a blacksmith shop and tavern. Painter himself helped to underwrite the cost of the latter, a two-story building that could accommodate twenty-five guests at a time and served as seat of the Addison County Court both before and after the construction of the courthouse. Where was the church then? The location of the church had been a principal feature of the long-lasting feud between Painter and Daniel Foot. Painter wanted it at the falls, Foot wanted it near his homestead at the center of town. Each side had its strong supporters who threatened to withdraw if the conflict were not resolved to their satisfaction. At the town meeting of 1788 Foot’s barn had been chosen as the best available site for worship, and in 1790 a site committee voted three to two in favor of a meetinghouse location near Foot’s homestead. The two were Painter and John Chipman, and they managed to block the final decision, so much to Foot’s anger that he withdrew the use of his barn and eventually became a Baptist. In 1794 worship moved out of Middlebury’s barns and into the newly completed Mattock’s Tavern, where it stayed until the completion of the suitably uncomfortable courthouse in 1798. By 1806 there was little question as to the location of the functional center of town, and Daniel Foot had moved on. Painter finally convinced his townsmen and picked the site at the head of Main Street. The lot was purchased from current owner Loudon Case, the tavern was moved down Seymour Street (and demolished in the twentieth century), and the town finally prepared to build its church. It was a bit embarrassing. There was Middlebury, a sophisticated and increasingly attractive and important town with mills, stores, fine homes, inns, a courthouse, and a college — but still no church. The embarrassment was remedied, however, by the construction between 1806 and 1809 of a church the town could never have considered in 1790 — one of the finest Federal Style (text with tooltip) a term generally designating the American architecture of the late eighteenth and early 19th centuries and here used with particular reference to the architectural fashion emanating from Boston at this time. It is characterized by planar simplicity and a refined delicacy in proportions and detailing. Decorative details (akin to those of the English Adam style and Wedgewood china) are ancient Roman in their inspiration. Perhaps the most characteristic feature of the style is a doorway composition with a fan light and sidelights churches in New England.

As head of the building committee, in 1805 Painter called on Lavius Fillmore, a Connecticut-born house joiner (text with tooltip) a skilled woodworker who was responsible for the finishing work and details on a building in the eighteenth and early 19th centuries. This position was in contrast to that of a carpenter, who in the same period was responsible for such heavy work on a building as erecting the frame. The joiner often had a designing role as well — architecture only emerging as a recognized profession in this country during the course of the 19th century who had built four previous churches (East Haddam, Conn., 1794; Middletown, Conn., 1798; Norwich, Conn., 1801; Bennington, Vt., 1804–1806) and, especially in the Bennington area, a series of magnificent houses. The Middlebury church was to be Fillmore’s masterpiece. Three years in the construction, budgeted at about $9,000 (some fifteen per cent more than the Bennington church), and financed by the sale of pews for cash, building materials, and livestock, the building was similar to but larger and more elaborate than its Vermont sister. The general mass of the church is based on meeting houses built by Charles Bulfinch in Taunton and Pittsfield, MA, in the late 18th century. Fillmore’s early refinement of this type in East Haddam so influenced the design published by Asher Benjamin in his 1797 Country Builder’s Assistant that for many years it was thought the Middlebury church was based on the Benjamin illustration. Many exterior details of the Middlebury church bespeak its ultimate descent from the work of the English architect James Gibbs, who published designs for his most famous church (St. Martin-in-the-Fields, London) in his Book of Architecture, 1728. This last was the source of the design for the most elaborate pre-revolutionary tower in New England, that of John Brown’s First Baptist Meeting House (1775) in Providence, R.I., which Fillmore almost assuredly had known well. He replicated that tower, famous for an ingeniously flexible, telescope-like (and thus wind-resistant) frame, timber for timber. Its effectiveness was proven in the hurricane of 1950, when 125 mile an hour winds tore off steeples across Addison County but left this tower unscathed. Fillmore studied his sources and then adapted and combined elements from them with a sure sense of detail and proportion to arrive a building that was his own. It was constructed by fifteen journeyman joiners, (text with tooltip) a skilled woodworker who was responsible for the finishing work and details on a building in the eighteenth and early 19th centuries. This position was in contrast to that of a carpenter, who in the same period was responsible for such heavy work on a building as erecting the frame. The joiner often had a designing role as well — architecture only emerging as a recognized profession in this country during the course of the 19th century who learned such details as the graduated width clapboards and graceful patterns of muntinwork (text with tooltip) muntin: a dividing element between the panes of a window in the windows and then utilized them to spread the Federal Style (text with tooltip) a term generally designating the American architecture of the late eighteenth and early 19th centuries and here used with particular reference to the architectural fashion emanating from Boston at this time. It is characterized by planar simplicity and a refined delicacy in proportions and detailing. Decorative details (akin to those of the English Adam style and Wedgewood china) are ancient Roman in their inspiration. Perhaps the most characteristic feature of the style is a doorway composition with a fan light and sidelights throughout the region.

The remarkably sophisticated galleried sanctuary (seating 725) was derived by Fillmore from another Bulfinch prototype, the short-lived Hollis Street Church in Boston, built in turn under the direct inspiration of Christopher Wren’s St. Stephen Wallbrook in London and famous for the acoustics of its domed ceiling “where he who sits farthest from the pulpit can hear as well as he who sits near.” Its basic rectangle has been skillfully manipulated through the use of groined vaults (text with tooltip) an arched ceiling in which various sections intersect to form sharp edges (or groins) into a cross with a central dome carried on a series of ionic (text with tooltip) Ionic order: the most graceful of the Greek orders. It is characterized by deeply fluted columns, capitals with spiraling volutes, and bands of dentils columns, each of which purportedly was cut from a single tree trunk in Court Square. Minor columns with Bulfinch-derived lotus capitals carry the gallery. Originally there was a raised pulpit before the Palladian window, (text with tooltip) a three-part window with a central arch between rectangular side openings. Popular in the sixteenth century in Italy, it was picked up by the English in the eighteenth century. It is also called the Venetian or Serlian window. and the pews were arranged in a semicircular fashion. These last aspects and others were significantly altered in 1854, when the entire interior of the church except for the shell, ceiling, and columns was reworked, with the sanctuary floor elevated to permit the development of usable spaces in the basement, the removal of the high pulpit, the Palladian window (text with tooltip) a three-part window with a central arch between rectangular side openings. Popular in the sixteenth century in Italy, it was picked up by the English in the eighteenth century. It is also called the Venetian or Serlian window. plastered over to control glare, and the replacement of box pews with slips. In 1925 the church interior underwent one of America’s earliest Colonial Revival restorations, bringing it back more closely to its original form.

In 1852 the town clock was installed in the tower, replaced by the present clock by the E. Howard Clock Company of Boston in 1891. In 1862 the organ was purchased from the firm of William A. Johnson of Westfield, MA. It had 1281 pipes, varying from one-half inch to sixteen feet in size. Electrified and augmented with chimes in 1943, it was rededicated in a concert by famous organist E. Power Biggs.

The product of controversy, sacrifice, and care, the church since 1806 has played a functionally as well as a physically central role in the life of the village. The frame and roofing were rushed to completion in time for the opening of the 1806 session of the state legislature in Middlebury, when townspeople and dignitaries alike sat on planks on kegs and shuffled their feet in the shavings. Since that date the church has served as a principal place for public meetings, dinners, and functions including, until 1937, the commencement exercises of the College (preceded by an academic procession up Main Street from the campus) and, until the 1990s, an annual Forefather’s Day celebration (the oldest in the nation, instituted by Phillip Battell and the Middlebury Historical Society in 1842.)

27 Emma Willard Monument The small triangle of land between the church, the Green, and the Charter House was dedicated in 1941 to Emma Willard, pioneer in women’s education. Middlebury, which had founded a male grammar school in 1797, decided in 1800 to do the same for females and invited Ida Strong to establish a female seminary in the courthouse. In 1803 a building was built for the new school with town contributions on a Seymour Street site donated by Horatio Seymour. Miss Strong died in 1804; and in 1807 the town invited Miss Emma Hart from Berlin, CT, to revive the enterprise. It was not an easy commission. Her first winter in town was so cold that she and the students spent a good deal of time contra-dancing to keep warm. In 1809 she married local doctor and man of affairs, John Willard, and retired from teaching to an impressive new house on South Main Street. However in 1812, as a result of a purported bank robbery of 1809, the directors (including Dr. Willard) were held personally liable for the repayment of the bank’s loss. The Willards were suddenly in financial straits, and Emma went back to teaching young ladies. This time the teaching was in her home and was directed not at a grammar school but rather at a collegiate level — the goal being to train teachers. The new curriculum, which Mrs. Willard published in 1818 as A Plan For Improving Female Education, included art (up to that time being taught academically in the United States only at West Point). At the invitation of Gov. DeWitt Clinton of New York, the Willards moved from Middlebury, eventually establishing themselves and Emma’s school in Troy, N.Y., where it became known as the first full-fledged normal school in America. The credit for the beginning of women’s collegiate education, however, is Middlebury’s (Middlebury’s and the bank robbery’s, that is). The monument to Mrs. Willard was designed by Vermont artist Marion Guild (later illustrator of Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer) as part of the Federal Arts Project under the Works Progress Administration and erected in 1941.